(*Linked or embedded content may have been removed or be unavailable.)

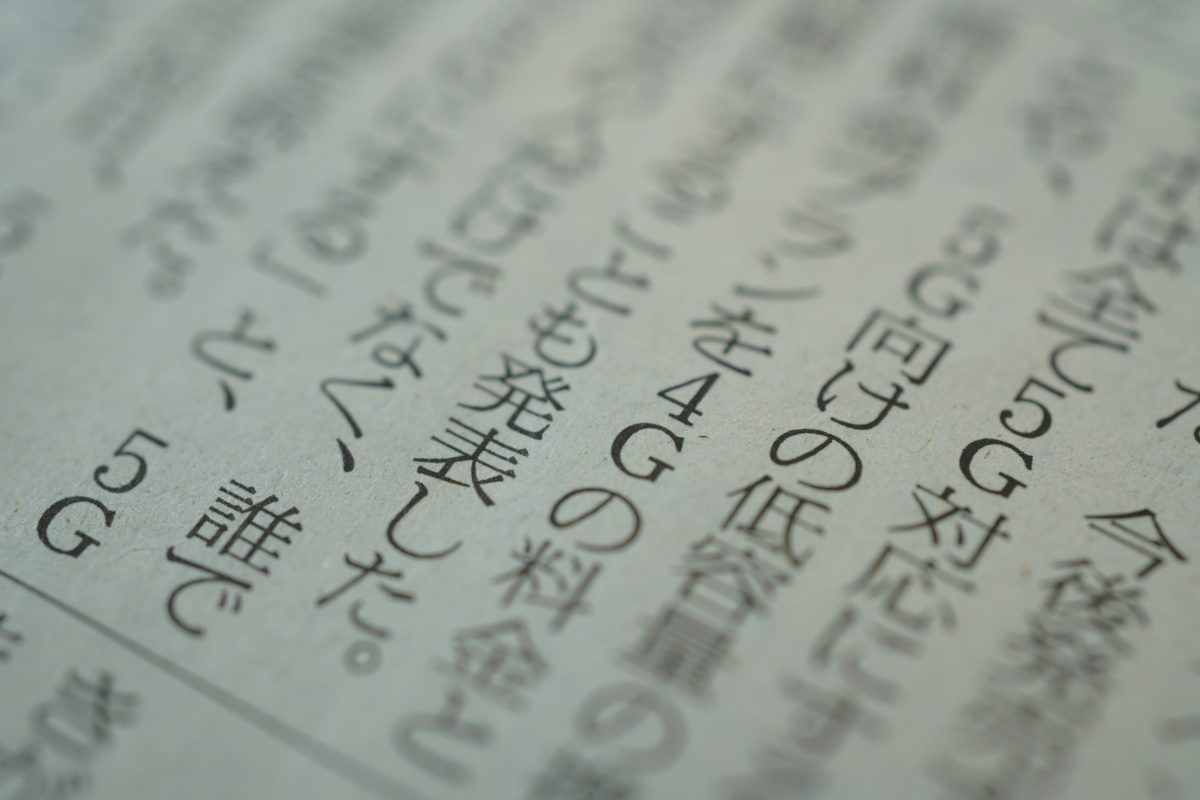

Japan has its fair share of foreign loanwords, that’s for sure. Unlike loanwords infiltrating Western languages, loanwords coming into Japan are generally easy to spot because they’re usually spelled out using katakana characters to set them apart from traditional Japanese. But of course, there are always exceptions. Some loanwords have been with the Japanese people so long (think hundreds of years) that they’ve found a spot in the Japanese lexicon that defies being written in katakana script. Read on for some notable examples.

Contents

Tempura (天麩羅, 天ぷら)

Alongside sushi and teriyaki, tempura is perhaps one of the most iconic of Japanese dishes known to the Western world. But the historical irony behind this dish and its name is its Western roots that even most Japanese people aren’t aware of.

The name “tempura” comes from the Latin word “tempora,” which refers to the Ember Days or fasting periods observed by Roman Catholics. The name entered the Japanese lexicon together with the deep-frying technique that was introduced to Japan in the 16th century by Portuguese missionaries. During these fasting periods, Catholics would abstain from meat and often ate fried vegetables and fish instead. The Japanese adopted this cooking method and, over time, developed it into the distinct and refined dish we know as tempura today.

The kanji characters 天麩羅 were chosen primarily for their phonetic value (to represent the sounds of the word “tempura”) rather than their literal meaning, but when we break it down, character by character, certain meanings may be inferred: 天 means “heaven,” “sky,” or “celestial”; 麩 means “wheat gluten” or “bran”; and 羅 means “gauze,” “silk (thin fabric),” “net,” or “to spread out.” So, with a little imagination, one can visualize batter-dipped morsels spreading out into the hot oil as they splash down.

And to be honest, compound words like “ebiten” (えび天, shrimp tempura), “tendon” (天丼, rice bowl topped with tempura) and “tenzaru”(天ざる, soba noodles with tempura on the side) only serve to fortify the image of 天 meaning “tempura” more than “heaven.”

Konpeitō (金平糖)

The name “konpeitō” comes from the Portuguese word “confeito,” which means “confection” or “candy” in general.

This popular Japanese sugar candy was introduced to Japan in the mid-16th century by Portuguese traders and missionaries. At that time, sugar was a rare and expensive commodity in Japan, making konpeitō a luxurious treat. There’s a famous story that in 1569, a Portuguese missionary named Luís Fróis presented a glass flask of konpeitō to Oda Nobunaga, a powerful feudal lord, to gain permission for Christian missionary work.

While the name is derived from Portuguese, the Japanese later developed their own unique way of making and enjoying this distinctive candy with its characteristic bumpy surface. The Japanese characters for konpeitō, 金平糖 (literally “golden flat sugar”), are mostly phonetic in purpose, but the inclusion of 糖 to show that it’s sweet and 金 to hint at its high value did help make it a permanent part of the Japanese lexicon.

Ikura (いくら, イクラ)

Perhaps you’ve seen this word on a sushi restaurant menu somewhere? The word “ikura” in Japanese means “salmon roe,” but it’s also a loanword from the Russian word “ikra” (икра). In Russian, “ikra” is an overall term for all types of fish roe or caviar in general. However, when the term was adopted into Japanese, it became specifically associated with salmon roe.

This linguistic connection highlights the historical ties and cultural exchange between Japan and Russia, particularly in the realm of seafood and fishing. While Japanese cuisine has a long history of consuming various types of fish and seafood, the specific practice of preparing and consuming salmon roe in the way that led to the “ikura” dish was influenced by Russian methods and terminology.

Kabocha (南瓜, かぼちゃ)

The Japanese word “kabocha,” which refers to a type of winter squash similar to pumpkin, has a fascinating origin that ties back to Portuguese traders and Cambodia. The timeline as to how kabocha became kabocha is interesting to say the least. Squashes, which were native to the Americas, were taken back to Portugal and cultivated during the early 16th century, which they later introduced to Japan in the mid-16th century.

This type of squash that became “kabocha” was named “Camboja abóbora,” meaning “Cambodia squash,” which the Japanese then shortened to “kabocha.” This reflects how the Portuguese sailors had likely stopped in Cambodia on their journey to Japan, leading to the association of the squash with that region. The kanji characters 南瓜 literally mean “southern gourd,” also giving us hints into kabocha’s migration to Japan by way of Southeast Asia.

Onbu (負んぶ, おんぶ)

The Japanese word “onbu” means “piggyback ride” or “carrying on one’s back,”and there are competing theories for its origins. One is that it’s a derivative of an older Japanese verb “obuu,” which means “to carry on one’s back.” But for the purposes of this blog post, there’s a more interesting theory which claims that “onbu” comes from the Portuguese word “ombro,” meaning “shoulder.” As for which theory to trust, it’s pretty much anybody’s guess.

It should be noted that when written as 負んぶ, the kanji character 負 has the meaning “to carry” or “to bear.”

Kappa (合羽, かっぱ)

The Japanese word for a raincoat, “kappa,” comes originally from the Portuguese word “capa.”

“Capa” in Portuguese means “cape,” “cloak,” or “jacket.” When Portuguese traders and missionaries arrived in Japan in the 16th century, they wore long capes and cloaks, which the Japanese then adopted as the term for their own rain garments.

It’s important to distinguish this “kappa” (raincoat) from the mythological creature also called “kappa” (河童), the amphibious humanoid often depicted in Japanese folklore. While they sound the same, their origins are entirely different. The creature’s name is native Japanese, derived from “kawa” (river) and “wappa” (child).

So, just like “tempura” and “kompeito,” the word “kappa” for a raincoat is another example of a significant loanword from Portuguese that entered the Japanese language during a period of early cultural exchange.

Karuta (歌留多. かるた)

The Japanese word “karuta” referring to traditional playing cards, comes originally from the Portuguese word “carta” for “card” or “letter.” Just like many other items and words introduced during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (mid-16th century), playing cards were brought to Japan by Portuguese traders and missionaries.

These early cards were used for gambling, and while the games and specific designs evolved over time, the name stuck. Over the centuries, “karuta” diversified into various types of Japanese card games, some of which are still popular today, such as Hanafuda and Uta-garuta (poetry cards).

Otenba (お転婆, おてんば)

The Japanese word “otemba,” meaning “tomboy” or “spirited/unruly girl,” is believed to have originated from the Dutch word “ontembaar,” taking root in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868). This Dutch word means “untamable,” “indomitable,” or “irrepressible.” The qualities described by “ontembaar” align well with the characteristics of a “tomboy”—a girl who is spirited, perhaps a bit wild, and doesn’t conform to typical feminine expectations.

The “o-” at the beginning of “otemba” is often a polite or honorific prefix in Japanese, but in this case, it might have been incorporated as part of the phonetic adaptation. The kanji お転婆 (literally “o-turn-old woman”) were chosen for their phonetic value rather than their literal meaning, as is common with many loanwords or words with folk etymologies.

Juban (襦袢, 繻絆)

The Japanese word “juban,” which refers to an under-robe worn beneath a kimono, originated from the Portuguese word “jibão,” meaning “jerkin” or “doublet,” a close-fitting jacket or vest, often worn as an undergarment.

As with many other words related to clothing, food, and daily life, the Portuguese introduced this type of garment (or the concept of it) to Japan during their period of significant trade and cultural exchange in the 16th century. The Japanese then adapted the word “jibão” into “juban” to describe the undergarment that became an essential part of traditional kimono attire.

Bateren (伴天連, 破天連)

The Japanese word “bateren,” an archaic term for a Christian missionary priest in Japan, originated from the Portuguese word “padre” meaning “father,” a common title for Catholic priests. When Portuguese missionaries, particularly Jesuits, arrived in Japan in the mid-16th century, the Japanese adapted this term to refer to them.

The kanji used for “bateren,” such as 伴天連 (literally “accompanying heaven connection”) or 破天連 (literally “breaking heaven connection”), are ateji. This means they were chosen for their phonetic resemblance to the Portuguese word rather than for any direct semantic meaning related to the kanji themselves. In many cases, these ateji were chosen to convey a sense of the foreignness—and even the perceived danger—of the new religion, back during that era in Japan’s history.

Konkurabe (根競べ)

Fake-news alert! Although the Japanese term “konkurabe” (meaning “contest of endurance”) momentarily became famous in the Japanese media this year as something related to “konkuraabe” (コンクラーベ, meaning “conclave”), most scholars have come to the conclusion that these two words are not related. The phonetic similarity which caused the confusion was purely coincidental although the timing was perfectly spot-on.

As we’ve seen with these examples of stealthy non-katakana loanwords in the Japanese language, they tend to have roots pre-dating the Meiji Restoration (1868) during which there was a major influx of Western loanwords and the systematic use of katakana script to transcribe them took shape. Such older loanwords originate primarily in Portuguese and Dutch because they arrived on Japanese shores when Japan’s contact with the outside world was limited mainly to Portuguese missionaries and Dutch traders. The result is a group of foreign-origin words that have assimilated themselves so thoroughly into Japanese society that even most Japanese people don’t recognize them as foreign.