(*Linked or embedded content may have been removed or may be unavailable.)

Part One

Translating between any two languages is bound to present challenges, be they grammatical differences, cultural barriers, or otherwise. But some are more difficult than others — like English and Japanese. Two languages that largely developed independently of one another, English and Japanese have little commonality in alphabet, cultural and social influence, grammar, and more. Japan’s close economic ties to English-speaking nations, however, means they’re two of the most common translation pairs one is likely to find.

The video game industry provides an effective lens through which to examine the challenges of English-Japanese translation. Following the video game crash of 1983, Japanese game company Nintendo took advantage of market turmoil to launch their iconic Nintendo Entertainment System in America two years later. The system’s smash success across the Pacific made the company a global icon, with the word “Nintendo” sometimes utilized as a generic trademark for video games, much like Xerox. And 40 years since that pivotal console launch, Japanese game companies and studios remain central to the global industry.

That tremendous impact wouldn’t be possible without the talented localization professionals — sometimes only one or two people tasked with translating huge texts — who made artistic works and product texts accessible for international markets. Localizing between English and Japanese has its challenges, but using the video game industry as a model, one can find interesting approaches toward overcoming them.

Japanese and English translation: a construction conundrum

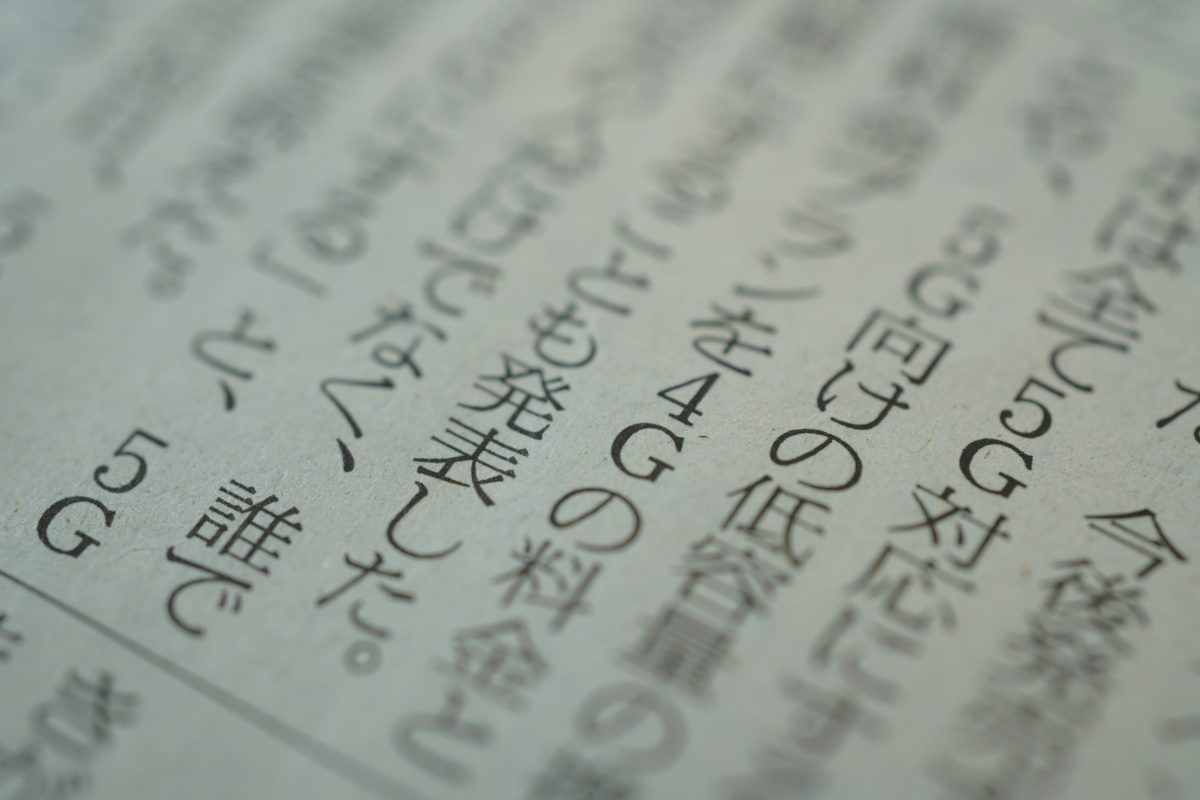

There’s no easy way to avoid the mechanical differences between English and Japanese. Two languages that evolved in isolation from one another for most of human history, their unique origins likewise produced unique forms and expressions. Where English largely gets by on the Latin-derived English alphabet alone, Japanese uses a mix of logographic Kanji and the Hiragana and Katakana syllabaries. Hiragana is used mainly for native words and grammatical elements, while Katakana is used primarily for loanwords, foreign names, and emphasis. And while English reads left to right, Japanese can either read horizontally from left to right or vertically from right to left. If you’ve ever seen a manga book that starts on the last page and ends on the first page, now you know why.

And the complexities don’t stop there. Japanese and English grammar systems flow in completely different ways. English sentence structure is SVO (subject-verb-object), whereas Japanese is SOV. Both may begin sentences with a subject, like “Thomas” or “I.” But where English would say “Thomas is riding the bike,” Japanese would say “Thomas the bike is riding.”

Then there are the smaller differences that can add up to big annoyances for translators. English has three verb tenses indicating the past, present, or future, while Japanese verbs distinguish only past and non-past. In Japanese, the future is usually understood from context or clarified with expressions like “tomorrow” or “in the future.”

Also, Japanese has no spacing between words, and it can often be highly space-efficient in communicating information. English, meanwhile, takes up to 60% more space on average. That can cause difficulties for translators when space is at a premium. Imagine being a linguist tasked with translating a 1990s Japanese role-playing video game’s text in dialogue boxes of set height and width — ask any professional involved in such work, and they’ll tell you about the creative complexity of making the translations fit!

There are yet more dissimilarities, like the fact that Japanese nouns do not inflect for number (singular/plural) in the way that English does. It instead relies on context, counters, or reduplication to express plurality. And then there are the pronoun differences, but perhaps that segues neatly into the next section.

The two languages’ structural differences cause no shortage of headaches for video game translators — particularly in the early days of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Translators grappled with technical and space limitations, word size differences, and grammatical tangles to make the games work in English, and translations in those decades often shipped with errors.

One memorable example is Squaresoft’s landmark RPG Final Fantasy VII; its original 1997 release contains a few errors, including a fondly remembered moment where a character observes of a slum-dweller, “This guy are sick.” In his video series Let’s Mosey: A Slow Translation of Final Fantasy VII for the gaming blog Kotaku, writer and game developer Tim Rogers speculates that the translator may have mistakenly translated the subject as plural but forgot to update the verb on the game’s spreadsheet.

But linguistic traits are just the beginning. Indeed, cultural differences between Japan and its English-speaking counterparts can create just as many complications. In part two, we’ll examine how culture impacts video game translation and what localization teams can do to bridge the divide.